In the Shadows of the Himalayan Mountains: Persistent Gender and Social Exclusion in Development

Introduction

Climate change in combination with socioeconomic processes and opportunities have an especially severe impact on people living in remote mountain areas of the Hindu Kush Himalaya (HKH). What is less well known is how changes in climate will affect in the quality of lives, livelihoods, and resources of diverse groups of people of the region.

This chapter argues that it is not only important but also necessary to link climate science and climate interventions with relevant contextual experiences of the different groups of people due their differential experiences and vulnerabilities.

This juxtaposition of climate change adaptation and everyday realities for farming households lead the authors to ask: what is it that farming households are adapting to, and what aspects of rural livelihoods are they adapting?

The chapter also provides illustrative cases studies to demonstrate the differential experiences and vulnerabilities of women and men as a result of the dynamics of gender relations in the context of climate change.

The text below is a summary of a chapter in the book: The Hindu Kush Himalaya Assessment: Mountains, Climate Change, Sustainability and People. For more detail, please download the chapter pdf on the right-hand column. This chapter can also be found on Springer here.

Key Findings

- Polices and responses in HKH countries overlook women’s multiple forms of oppressions and exclusions. Since women and men in the region are a heterogeneous group, they have overlapping ethnic, class, and caste identities that result in multiple forms of marginalization and exclusion. However, too many simplifications and one-dimensional framings around women’s identities—and people—persist, and policies and responses end up overlooking multiple forms of oppression and exclusions.

- Existing laws and policies do not support the multiple ways in which women negotiate their roles in households, communities, and the market. This is because men from the mountain regions are out-migrating in large numbers leaving women to manage not just household work but also other work related to agriculture, natural resource management, community and even other public sphere related work—markets or public institutions—that were traditionally men’s role. As an example, land tenure and employment policies undervalue rural women’s critical roles in food security, sustainable agriculture, and natural resource management despite women taking on the major role in these sectors.

- Women throughout the HKH do not have corresponding decision-making rights or control over resources despite shouldering both productive and reproductive workloads and responsibilities. This results in undervaluation of their work in society and therefore not taken into account in most policy making processes and outcomes.

Case Studies

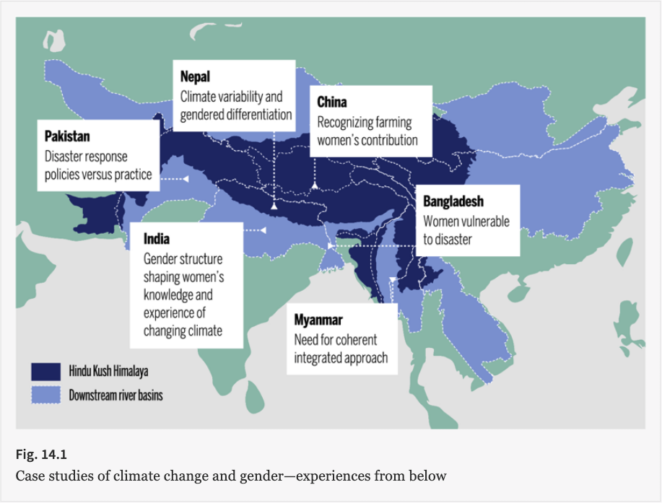

Due to a lack of large-scale data, and a lack of cases from all HKH countries, we focus on illustrative case studies to show the interlinkages between gender and climate change. Some specific case studies presented from India, Nepal, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Myanmar, and China highlight the manifestation of gender vulnerability and women’s roles from the HKH (see Fig. 14.1).

Policy Messages

- Policies that support adaptation to climate change will not succeed unless they consider gender and how it interacts with other factors such as class/caste, ethnicity, and geography, which will require disaggregated data. The available national data on women in HKH countries does not reflect the diversity and intersectionality, because they rely on aggregate measurements and aggregated country data that may not be representative of the mountain areas. It is critical that disaggregated mountain specific data be collected and analysed to inform policies that are suitable.

- Policies to improve women’s participation in decision making and climate governance must go beyond numbers and quotas to create mechanisms that ensure empowerment and promote women’s rights and agency. Given the fragile and dispersed nature of settlements in the HKH, facilitating women’s active voice and agency will equally require working with gender responsive grassroots organizations and nurturing local and inclusive leadership, (i.e. top-down and bottom up approaches).

- All levels of government must allocate resources—financial and human—for gender responsive interventions at scale and adopt clear accountability mechanisms, such as gender budgeting, to demonstrate their commitment to gender equality as indicated in the SDGs. Most countries in the HKH lack gender budgeting and accountability mechanisms on gender—almost all government agencies are male-dominated and gender neutral.

Conclusion

This chapter has shown that climate change and extreme weather have differential impacts on women and men in the HKH. The case studies confirm that women’s experiences in the HKH are multiple, differentiated, and sometimes contradictory and, in some cases, effect new chains of vulnerability.

Women across different socioeconomic categories are disproportionately affected because of structural inequalities in the distribution of rights, assets, resources, and power based on repressive cultural rules and norms. As a result, women are often poorer and less educated than men and excluded from political and household decision-making processes at various scales that affect their lives.

In conclusion, the authors set forth a vision of inclusive development for the HKH complementing, and in the spirit of, the Sustainable Development Goals adopted by the global community in 2015: By 2030, environmental governance processes, policies, and strategies at scale (from local to global) are gender inclusive and cognizant of the mosaic of nested, uniquely diverse, dynamic, and mostly gender-inequitable socio-ecological systems in the HKH.

Suggested Citation

Resurrección B.P. et al. (2019) In the Shadows of the Himalayan Mountains: Persistent Gender and Social Exclusion in Development. In: Wester P., Mishra A., Mukherji A., Shrestha A. (eds) The Hindu Kush Himalaya Assessment. Springer, Cham.

- See this paper on Springer Link

- Read the book: The Hindu Kush Himalaya Assessment (open access)

- Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment Report: Developing a Demonstration Site in Nepal on Community Forestry, Gender and Clima

- Impacts of Climate Change on the indigenous Majhi community in Nepal

- Safer lives and livelihoods in mountains: Making the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction work for sustainable mountain

Comments

There is no contentYou must be logged in to reply.