The Climate-Cryosphere-Water Nexus in Central Asia

Introduction

The cryosphere – the frozen water component of our planet – will undergo dramatic changes in the future if anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise unchecked. Even if the global community achieves the 1.5–2°C aspirational goal set by the Paris Agreement, changes in the cryosphere will be massive.

In the predominantly dry climate conditions of Central Asia, the role of the cryosphere is particularly important for water resources. The main sources of water in Central Asia are the Syr Darya and Amu Darya rivers, which are mostly fed by snow melt and glacier meltfrom the Pamir, Hindu Kush and Tien Shan mountain ranges.

The Syr Darya and Amu Darya rivers are at the heart of socio-economic development in Central Asia, supplying water for domestic and municipal uses, industrial processes, agricultural production and hydropower. Each sector is intrinsically linked, with water generating about 22% of the region’s electricity supply and the rivers accounting for 75% of the irrigated agriculture in the region.

This nexus brief explores the interactions between changes in the cryosphere due to climate change and the consequences for water resources and hazard management in Central Asia. It analyses the status of those changes and discusses policy responses and implications for development and cooperation.

Facts & Figures

The warming across Central Asia is expected to exceed the global average, with the southernmost areas experiencing the greater shift in temperatures and the northernmost parts showing a less pronounced shift.

Future changes in precipitation exhibit a pattern where southwest regions, particularly parts of Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Afghanistan, may become drier whereas northwest regions, particularly parts of Kazakhstan, become wetter. Thus, the “dry-getting-drier and wet-getting-wetter” under climate change is a reasonable approximation.

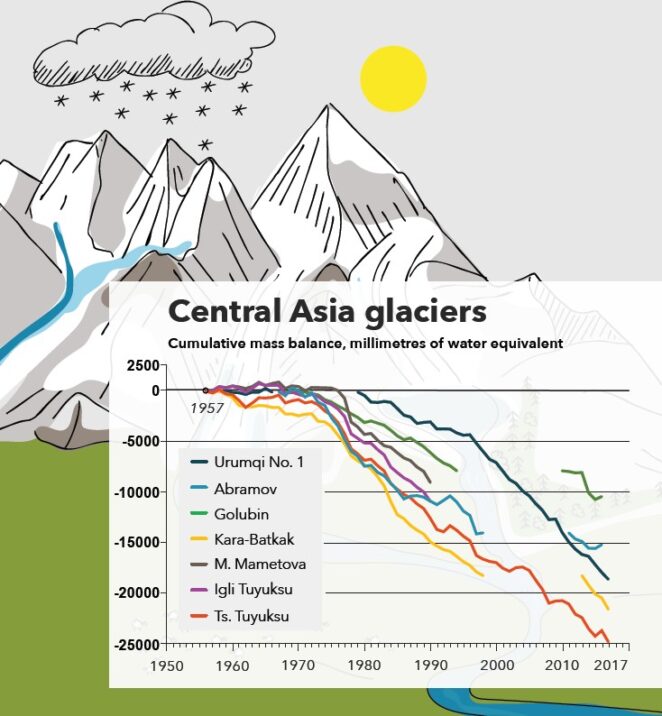

Observations provide clear evidence (Figure 2) that glaciers are retreating in response to global temperature increases. Glacier mass loss by the end of the 21st century is expected to be on the order of 50% in the low emission climate scenario and up to 67% for the more pessimistic scenario when compared to the present.

Global warming is expected to decrease snow cover and to cause more precipitation to fall as rain rather than snow. Studies assessing future snow and permafrost changes for Central Asia are rare, and accurate predictions for specific parts of the region are difficult to make. Nevertheless, there is agreement that snow cover is likely to decrease in the Northern Hemisphere.

Changes in seasonality and the amount of fresh water from glacierised and snow-fed run-off have serious implications for water availability and thus for the future management of transboundary water resources, such as those from the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers. Changes in water-related hazards.

The retreat of glaciers can result in the formation of lakes that are prone to devastating outburst floods that can lead to extensive damage. The thawing of permafrost may increase the region’s sensitivity to associated mass movements such as rock avalanches and debris flows. Furthermore, heavy rainfall events can combine with snow and glacier melt to form floods and subsequently threaten downstream regions.

Water management issues and policy responses

Key challenges in a nutshell

The challenges to water resources management in Central Asia include the complex transboundary character of the region’s rivers and the inherited Soviet irrigation and energy-for-water trading scheme for managing the allocation for water, energy and food:

- With upstream countries investing incrementally in their hydropower potential, the original system of allocation, primarily designed to support the irrigation regime, could not accommodate all the riparian interests.

- In the post Soviet transition, the Central Asia republics have faced economic constraints that resulted in a lack of investment in infrastructure and a failure to modernize institutions.

- Institutions, such as the International Fund for Saving the Aral Sea (IFAS), have played a critical role in maintaining a platform of dialogue and cooperation for addressing the environmental impacts of the Aral Sea crisis. By its nature, IFAS is unable to adjust to rapidly evolving political realities and economic projects. Development partners have proposed and supported reforms, but no significant progress on structural changes has been achieved.

- Currently all the Central Asia republics are making water sector reforms and introducing good practices, such as Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM), at the national level. Since 2017, Central Asia has been experiencing a renewal of regional dialogue for cooperation. This dialogue could open new opportunities for cooperation.

Status of climate change adaptation

Climate action is gaining in importance and is increasing awareness of the climate risks and impacts on economies and livelihoods. With the exception of the Kyrgyz Republic, the Central Asian countries have signed and ratified the Paris Agreement.

The role of glaciers is also increasingly recognized as part of climate action, and several Central Asia countries are strengthening academia and research efforts.

- The Scientific Center for Glacier Research opened in Tajikistan in 2018 and several other institutes are in place, although capacities remain limited.

- In Kyrgyzstan, sectoral climate change adaptation programmes have been established for agriculture, water resources and energy, health, forests and biodiversity,

- In Tajikistan, the development of water user’s association (WUA) is reflected in local policies for the implementation of climate change adaptation.

- In 2013 Kazakhstan launched a concept for a transition to a green economy as a tool to implement climate adaptation actions and to diversify the economy.

Key Issues

- Key issue 1: Expected changes in the Climate-Cryosphere-Water nexus. Cryosphere-related changes to water resources will be minor over the next 10–20 years compared to the massive changes expected later in the century as snow extent and duration decline and glaciers become significantly smaller or disappear. Changes in the timing and seasonality of water run-off from the mountains and changes in water quantity and quality will have major socio-economic consequences,with implications for future economic development in irrigated agriculture and hydropower in the region.

- Key issue 2: Water management issues in transboundary settings. Future changes in water availability resulting from climate change call for transboundary coordination of water resources management, planning and distribution. The water-energy-agriculture-climate nexus approach has been identified as a possible way for the Central Asian states to enhance their dialogue and cross-border cooperation. The nexus approach advocates the use of integrated resources management to respond to the impacts and risks of climate change.

- Key issue 3: Improving scientific knowledge and hydrometeorological monitoring networks. The considerable uncertainties associated with the scientific evidence on climate and the cryosphere in the region are mostly attributable to inadequate monitoring and measurements – few long-term glacier measurements and spotty data on changes in run-off. Steps are already underway to close the gaps and to build capacity among a new generation of local hydrologists, meteorologists and climate scientists.

Key Messages

The mountain cryosphere is already changing and will continue to change considerably towards the end of this century, depending on emission pathways. Risks related to water scarcity and changing hazards need to be assessed in the context of climatic and non-climatic drivers in order to devise appropriate adaptation solutions.

Transboundary cooperation and integrated approaches in water management are key strategies in the development of sustainable adaptation solutions in the region. Integrated Water Resources Management through the implementation of basin management principles is a key instrument for maintaining interstate dialogue and an entry point to the climate-cryospherewater nexus.

Excellent examples of projects and programmes relevant to development and cooperation in the region are testimony to the willingness to step up adaptation solutionsthat are integrative and robust, and that address unexpected changes.

Suggested citation

Muccione, V. and Cassara, M. 2019. The ClimateCryosphereWater Nexus in Central Asia. Issue Brief on Sustainable Mountain Development. Nexus Brief, Nr. 8, October 2019 Climate Change & Environment. Bern, Switzerland: SDC Climate & Environment Network.

Further reading

- Nexos entre el clima, la criosfera y el agua en Asia Central (2019)

- Система взаимосвязей «климат – ледовый покров – вода» в Центральной Азии (2019)

- Le lien Climat-Cryosphère-Eau en Asie Centrale (2019)

- Read the issue brief "Shaping the water–energy–food nexus for resilient mountain livelihoods"

- Read the report "Safer lives and livelihoods in mountains"

- Read the report "Making governance work for water-energy-food nexus approaches"

- Read the report "Managing disaster risks and water under climate change in Central Asia and Caucasus"

- Explore the Indian Himalayas Climate Adaptation Programme and its ouputs

- Explore the "Glaciology Curriculum"

- Explore the Himalayan Adaptation, Water and Resilience (HI-AWARE) project and outputs

Comments

There is no contentYou must be logged in to reply.