Transboundary climate risks and adaptation in mountain areas: a brief for Parties and Observers to the UNFCCC

Summary

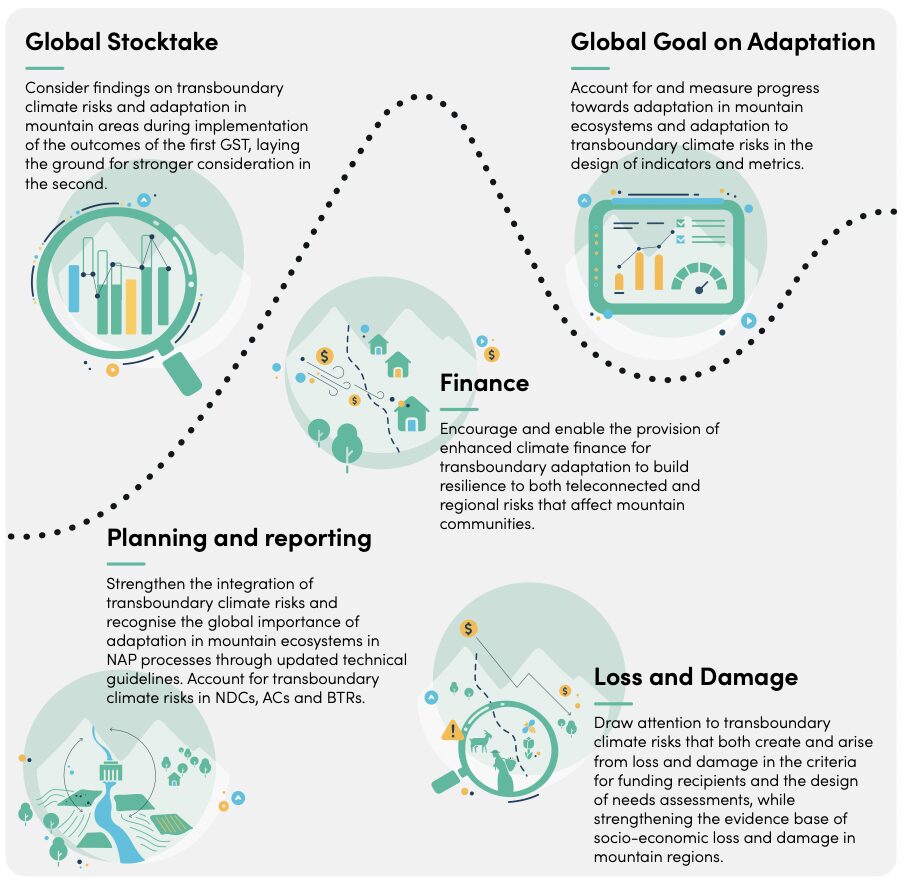

This policy brief, developed in collaboration with Adaptation without Borders and Adaptation at Altitude, highlights engagement opportunities for UNFCCC Parties and Observers to bring in transboundary climate impacts and climate change adaptation in mountain areas across relevant negotiation tracks: Global Stocktake, Global Goal on Adaptation, Finance, Planning and reporting, and Loss and Damage.

You can also read a summary of our ‘negotiator asks’, also attached as a document on the right-hand side.

This article is an abridged version of the original text, which can be downloaded from the right-hand column. Please access the original text for more detail, research purposes, full references, or to quote text.

Why this brief?

Transboundary climate impacts, and the risks they generate within and beyond mountain areas, are of rising concern in international climate change negotiations. These risks are highly relevant to the adaptation needs of all countries.

This brief is intended for Parties and Observers to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). It articulates what transboundary climate risks are, why they matter, and their relevance for different negotiation tracks – including proposed calls for action.

These negotiation tracks represent important and appropriate entry points for raising transboundary climate risks and advancing the mountain agenda at the upcoming United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP29) and beyond.

With many groups making transboundary climate risks a priority – even working towards the development of common positions – negotiators have an opportunity to raise the specific needs and concerns of their countries and take steps to assure their region’s future climate resilience.

The rationale: raising transboundary climate risks and the adaptation needs of mountain communities at COP29 and beyond

There is a strong rationale for negotiators to raise transboundary climate risks and the adaptation needs of mountain communities at COP29 and beyond. We provide three compelling arguments.

- Transboundary climate risks and adaptation in mountain areas are increasingly highlighted in Party submissions to the UNFCCC. Many countries are already a part of this growing and diverse coalition. But strengthening the world’s resilience to transboundary climate risks will require bold and coordinated efforts.

- Transboundary climate risks and adaptation in mountain areas are gaining increasing traction on the world stage. There is momentum to harness but also a risk of deepening long-held divides.

- Raising transboundary climate risks and adaptation in mountain areas in the negotiations could lead to breakthroughs on otherwise intractable negotiating issues.

To read further information please see pages 3-5 of the brief, available to download on the right hand side.

Entry points in UNFCCC negotiation tracks at COP29 and beyond

We identify five negotiation tracks at COP29 and beyond that represent important and appropriate entry points for raising transboundary climate risks and advancing the mountain agenda. For each track, we propose concrete recommendations, describe relevant contextual developments, clarify the specific case and rationale, and point to further resources.

The Global Goal on Adaptation and UAE Framework for Global Climate Resilience

- Indicators for measuring progress achieved towards the targets of the UAE Framework for Global Climate Resilience should extend beyond national markers of progress to also assess cooperation and resilience-building efforts between countries.

- Indicators should also capture progress towards protecting global public goods, such as mountain ecosystems, recognizing the global implications of localized climatic effects: this will require a structured approach.

- If the UAE–Belém Work Programme fails to account for transboundary climate risks, future assessments based on the UAE Framework for Global Climate Resilience will create an incomplete and misleading impression of the scale and nature of the adaptation challenge. They will significantly underestimate the total risk faced by countries, and fail to capture the clear and present dangers to equity and justice created by transboundary climate risks. They will also fail to capture the positive contribution of local and national adaptation efforts to global resilience.

- Developing indicators to measure “just resilience” should be integral to the UAE–Belém Work Programme, helping ensure adaptation investments are more equitable and ultimately effective.

Explore the concrete recommendations and in-depth rationale for this track on pages 5-6.

The Global Stocktake

- The second Global Stocktake must go further than the first – not only acknowledge transboundary climate risks and the impacts of climate change in mountain areas but also assess levels of progress in adapting to them. Such assessments do not yet exist.

- To incentivise their development, Parties need to start identifying and communicating their needs for support to assess and manage transboundary climate risks now – at COP29 and COP30.

- Implementation of the first Global Stocktake decision presents a concrete opportunity to strengthen international cooperation and regional institutional mechanisms on adaptation. These have the potential to yield multiple co-benefits, including reduced climate risk, lower costs and fewer resource constraints, as well as enhanced knowledge and data exchange

Explore the concrete recommendations and in-depth rationale for this track on page 7.

Planning and Reporting

- The NAP assessment provides an opportunity to consider the alignment of NAPs, and respective national monitoring, evaluation and learning systems, with the priorities established through the UAE Framework for Global Climate Resilience and identify both gaps and needs. Those priorities, gaps and needs should account for transboundary climate risks and mountain areas, given their reference in the framework.

- NAP processes could serve as a critical mechanism to identify the transboundary climate risks that countries face and articulate actions to address them.

- Updates to the LEG technical guidelines present an opportunity to guide countries on how to integrate both transboundary climate risks and climate risks to mountain areas into climate risk assessments and national adaptation planning processes.

- Signalling collective recognition of the importance of transboundary climate risks and adaptation in mountain areas at COP29 could also encourage countries to reflect their resulting needs and circumstances in the adaptation sections of their BTRs – due at the end of 2024 – and updated NDCs – due early 2025.

- They could also incentivize countries to use their adaptation communications and national communications to highlight how they are responding to transboundary climate risks, and considering vulnerable ecosystems, in their adaptation efforts.

Explore the concrete recommendations and in-depth rationale for this track on pages 7-9.

Finance

- With transboundary climate risks and mountain ecosystems cited in the Global Stocktake and the UAE Framework for Global Climate Resilience, their inclusion in decisions related to climate finance represents a natural progression.

- To date, only a small proportion of multilateral adaptation finance has been allocated to address transboundary climate risks.

- Research also suggests that only a small portion of funding for mountain adaptation flows to the most vulnerable countries.

- COP29 represents an opportunity to raise the profile of these dynamics in the negotiations and start to shift international finance towards building “systemic resilience” that supports long-term international cooperation.

Explore the concrete recommendations and in-depth rationale for this track on page 9.

Loss and Damage

- As the structure and funding modalities of the new loss and damage fund are in the process of being negotiated, there is an opportunity to ensure that loss and damage funding considers and accounts for transboundary climate risks, including in mountainous regions.

- Transboundary climate risks could cause loss and damage if adaptation limits are reached; transboundary climate risks could also be a consequence of loss and damage if the effects ripple out to others.

- One contentious topic within loss and damage negotiations is which countries and communities should be eligible for funding support. Traditional measures of vulnerability only account for a country’s direct exposure to domestic climate change impacts. But we dramatically underestimate vulnerability unless we also account for a country’s exposure to transboundary climate impacts.

- But it also implies the converse may be true – that it may be possible to benefit from loss and damage recovery measures even if a country is not the direct recipient. This theory – transboundary or systemic resilience – augments the argument for a more programmatic approach to determining the distribution of loss and damage finance.

- Programmatic finance – as opposed to project-base finance – is also likely to be more practically suited to the task of responding to the loss and damages associated with transboundary climate risks.

Explore the concrete recommendations and in-depth rationale for this track on pages 10-11.

Recommendations for Observer Organizations

There were 3,804 organizations (3,631 NGOs and 173 IGOs) admitted as observers to COP28. As representatives from business and industry, environmental groups, farming and agriculture, Indigenous Peoples, local governments and municipal authorities, research and academic institutes, labour unions, women and gender and youth groups, their actions are critical to raising issues on the agendas of the United Nations Climate Change Conferences.

We outline 9 recommendations for observers to directly support negotiators to implement the recommendations in this brief and create a strong enabling environment to strengthen their uptake and amplify their impact. There are countless opportunities on the road to COP29 and COP30 to advance the mountain agenda and strengthen international cooperation on adaptation to transboundary climate risk. All it requires of us is to harness them.

To read further information please see page 11 of the brief.

Transboundary climate risks and adaptation in the Hindu Kush Himalaya

Transboundary climate risks have the potential to severely the societies, economies, and ecosystems of the Hindu Kush Himalaya. Some of these risks originate within the Hindu Kush Himalaya, requiring regional collaboration, but some originate beyond it and can only be addressed through international cooperation and diplomacy.

There is a strong rationale for negotiators of the Hindu Kush Himalaya to raise transboundary climate risks and the adaptation needs of mountain communities at COP29 and beyond.

For more information on how the brief’s recommendations are relevant in the context of the Hindu Kush Himalaya (HKH), you can read our HKH-facing brief which is also available to download on the right-hand side.

Suggested Citation:

Harris, K., Williamson, K., Klein, R. J.T., Shawoo, Z., Browne, K., Mackey, A. and Zwahlen, J. (2024). Transboundary climate risks and adaptation in mountain areas: shaping the global agenda in 2024 and beyond. Adaptation Without Borders Policy Brief 3. Stockholm Environment Institute.

Comments

There is no contentYou must be logged in to reply.